Twomey presents Three Stage Drawing Transfer research at SIGGRAPH

calendar icon28 Sep 2022 user iconBy Kathe C. Andersen

Lincoln, Neb.--Robert Twomey, assistant professor of emerging media arts in the Johnny Carson School of Theatre and Film, presented his research project, “Three Stage Drawing Transfer” at SIGGRAPH in August.

SIGGRAPH is the premier conference for computer graphics and interactive techniques worldwide. The conference showcases new technologies and applications.

In addition to presenting and publishing his research, Twomey also showed Three Stage Drawing Transfer in the art gallery program at the conference.

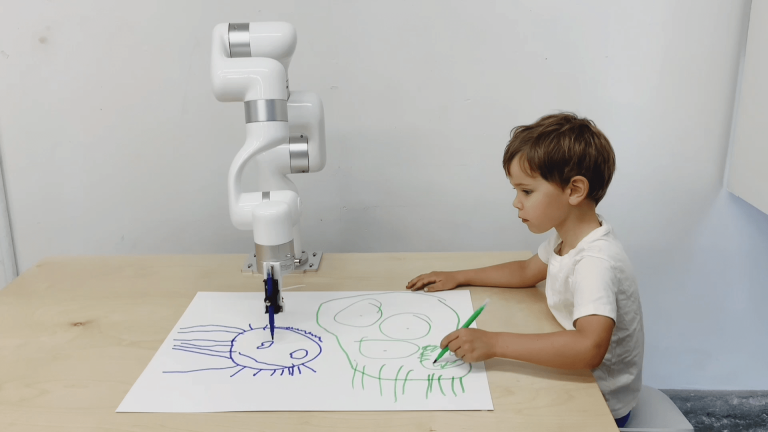

Three Stage Drawing Transfer is a collaborative drawing between a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN), a co-robotic arm and a five-year-old child. In his paper published at the conference, Twomey describes it as “an experimental human-robot performance and emerging media arts research project exploring drawing, cognition and new possibilities for creative, embodied interactions between humans and machines.”

“I’ve been interested in machine learning and creative AI (artificial intelligence) for a while, and I approach it through a human-centered lens,” Twomey said. “Since I started learning about training neural networks that generate images, I’ve had this idea of training a neural network to generate children’s drawings because I like that there’s kind of this explicit juxtaposition between human and machine learning. I think also that there’s an alienness, a kind of mystery in doodles and scribbles, things that are sort of pre-linguistic or unschooled.”

The title of the project refers to Dennis Oppenheim’s 1971 artwork “2 Stage Transfer Drawing,” an inspiration for Twomey’s work. In that piece, Oppenheim staged a photographic drawing performance with his son. In the first image from the project, his son traces on the artist’s back, and Oppenheim tries to recreate that drawing on the wall. In the second image, Oppenheim traces on his son’s back, who then attempts to reconstruct Oppenheim’s drawing based on his own physical perception.

“I wanted to train a neural network on children’s drawings, and I have these other projects that I’ve done in the past that use children’s language and children’s drawings in different ways,” Twomey said.

Psychologist and nursery school educator Rhoda Kellogg published an archive in 1967 of approximately 8,000 drawings of children ages 24 to 40 months from the more than 1 million children’s drawings she collected from 1948 to 1966, which Twomey used to train his neural network.

“I started working on that neural network, working with this database of child art from this child art researcher Rhoda Kellogg, and then it was sort of what to do with it?” Twomey said. “So, on one hand, I made some experimental animations that are visualizing the imagination of that neural network. I’ve worked with drawing machines and robots in different ways. Since I started here, I’ve been working with this co-robotic arm, so there’s this opportunity to take something that exists within the neural network and render it in a physical space. I’ve also been interested in working with family and kind of an intimate or domestic space.”

He drew inspiration from Oppenheim’s work with the idea of drawing as communication or an embodied exchange in a familial context.

“That’s where I had this idea that I could set up a relationship between the neural network, the robot and my son,” he said. “By proxy, I’m doing that sort of like a drawing exchange or transfer. But this one, there’s all these anonymous children who contributed drawings that I used as training data. There’s this robot that my son’s interacting with.”

Twomey said there is more to do with the project as it continues.

“The one I’ve shown so far, the robot is initiating the drawing. It’s kind of like the neural networks dream up an image, the robot is drawing it, and the humans respond to that,” he said. “But what I like about that Dennis Oppenheim piece is that it goes in both directions. What I’ve been doing is taking my son’s drawings, starting with his images, and projecting those into the neural network. So how does the machine reimagine what he drew or respond to what he drew, so that the human child can initiate it.”

Turning it into an interactive experience adds another layer of complexity to the project.

“This robot arm has a camera on the end, so it can notice if you’re there, and it can see what’s been drawn,” Twomey said. “I think there’s something special that comes from its embodiment that’s different from something that occurs on a screen or in a printer in documentation. None of us knows what’s going to come out of the robot or out of the neural network, so it’s kind of a question mark for all of us. There’s something really compelling for me in my son’s active perception and interpretation of what it’s drawing. This idea of reading something into it is interesting and is that kind of juxtaposition of human and machine perception.”

Twomey also presented Three Stage Drawing Transfer at ISEA 2022 (International Symposium on Electronic Art) in Barcelona, Spain, in June, along with another collaborative project with Assistant Professor of Emerging Media Arts Ash Eliza Smith and Assistant Professor of Practice in Emerging Media Arts Jinku Kim.

“Ash and I had done a project earlier in the fall that was an AI writer’s room that was part of the Flyover Conference that she organized,” Twomey said. “For that event, we had 10 students and we worked with GPT3, a state-of-the-art language AI. Throughout the day, the students prompted the AI to speculate or invent these narratives around the events of the day.”

It was published on the Carson Center’s Twitter feed, and Twomey and Smith began exploring the idea of co-writing with AI and exploring what the machine brings to that human-machine co-authorship.

“We both had this longstanding interest in radio plays as a form, and so starting in the fall, Ash, Jinku and I started doing a few sessions where we would work with GPT, bring in audio, reading the results and improvising with our voices,” he said. “We started to sketch out what a radio play would be like that’s being written and performed by humans in concert with this AI.”

During ISEA, they created a workshop titled Radio Play.

“Over the course of eight hours, we introduced people to the idea of speculative worldbuilding. We introduced the ideas of these large language models and how you co-write with them,” he said. “We decided on some plot points and fleshed in episodes around a central narrative. We had about 20 participants. We produced four-to-five-minute vignettes with interstitials and announcements. Over the course of a day, we produced this radio play and broadcast it. It was a tremendous success.”

They will repeat the workshop this fall at the Society for Literature, Science and Arts at Purdue University in October, where they will do another broadcast.

“It’ll be kind of episodic, but with new subject matter,” Twomey said.

They are also planning workshops for Los Angeles and Lincoln in the next year.

Their other collaborator is Stephanie E. Sherman from Central Saint Martins in London.

“Stephanie has this ongoing nomadic radio station, so we’re connecting up with this idea of community or DIY radio that travels and broadcasts on the internet,” he said. “We’re taking a similar thing but doing more of a stage performance.”

Twomey said working with this text-generation technology, there’s something about radio to experience text through voice and through sound.

“It frees up your visual imagination,” he said.